Refugee Movement – The View from Inside on Display

The exhibition “We Will Rise” by the Berlin Refugee Movement is both a documentation of the movement’s political struggle and the foundation of an archive about refugee life in Germany. With dozens of text boards and multi-media documents, the exhibition presents a comprehensive and chronological history of the movement from the refugees’ point of view: their struggle for dignified living conditions, integration and basic liberties. Accompanying the installation, the movement has produced a multi-lingual magazine with testimonies and detailed insights to every action they have organised, to give voices from within the movement an outlet and increase their public self-presentation. “We Will Rise” is on display at the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg-Museum until 30 October 2015.

Opening of the exhibition on 7 August at FHXB-Museum.

Opening of the exhibition on 7 August at FHXB-Museum.

From Refugee Strike to Refugee Movement

October 6th this year marks the third anniversary of the arrival of the Refugee Movement in Berlin. The “March on Berlin” started in September 2012 in Würzburg, eight months after the suicide of the 29-year old Iranian Mohammad Rahsapar in a local refugee center. His death pushed refugees in Würzburg to form a protest camp in the city to demonstrate against the asylum policy of Germany, the treatment of refugees by the state authorities and their isolation due to their non-citizenship. To express their despair and anger they engaged in radical public actions like hunger strikes, permanent sit-ins and sewing up their mouths. Inspired by this example, refugee protests spread all over Germany during the summer of 2012 and finally sparked a public debate about the living conditions of asylum seekers in Germany.

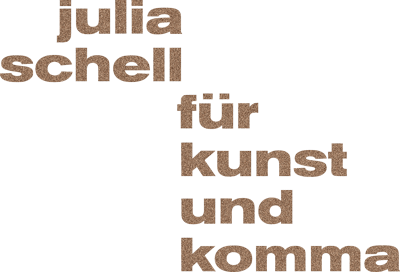

Demonstration and protest leaflets from the archive are on display in the exhibition.

Demonstration and protest leaflets from the archive are on display in the exhibition.

Escaping their physical and social isolation, refugees began to network, funnel their demands and start a joint public protest – the so-called “Refugee Strike” or “Refugee Tent Action”. Since neither authorities nor media did engage in dialogue with them yet, the self-organised refugees left their assigned districts in an act of political disobedience and embarked on the “March to Berlin”. At the time, the so-called ‘Residenzpflicht’ (mandatory residence) was still in full force, disallowing asylum applicants and those with a temporary stay (“Geduldete”) to leave local/district boundaries. “Berlin is where all the political institutions lie, that’s why we came here”, explains Bino Byansi Byakuleka, one of the leading figures and spokespersons of the movement, at the opening of the exhibition. The march finally gained nationwide media attention and marked a milestone in the movement’s development: political authorities and institutions could no longer ignore them.

Original banner from the early days of the movement and exhibition banner.

Original banner from the early days of the movement and exhibition banner.

Occupy Berlin and Public Demands

After a month and hundreds of kilometers on feet or in buses, around 70 refugees and 100 supporters from all over Germany arrived in the capital city. Once in Berlin, the refugees occupied Oranienplatz and built a tent town. Now, in the eye of the public, authorities started to engage in dialogue with the refugees, with the local district mayor Franz Schulz (Green Party) officially exressing sympathy for the demands of the refugees. However, authorities were merely tolerating the camp and did neither accept nor offer ultimate and fast solutions regarding the status of the refugees, a core demand of the latter. So, some of the refugees started a hunger strike at Brandenburger Tor and later occupied the Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule in Kreuzberg as the negotiations stagnated over winter and solidarity from the civil population increased.

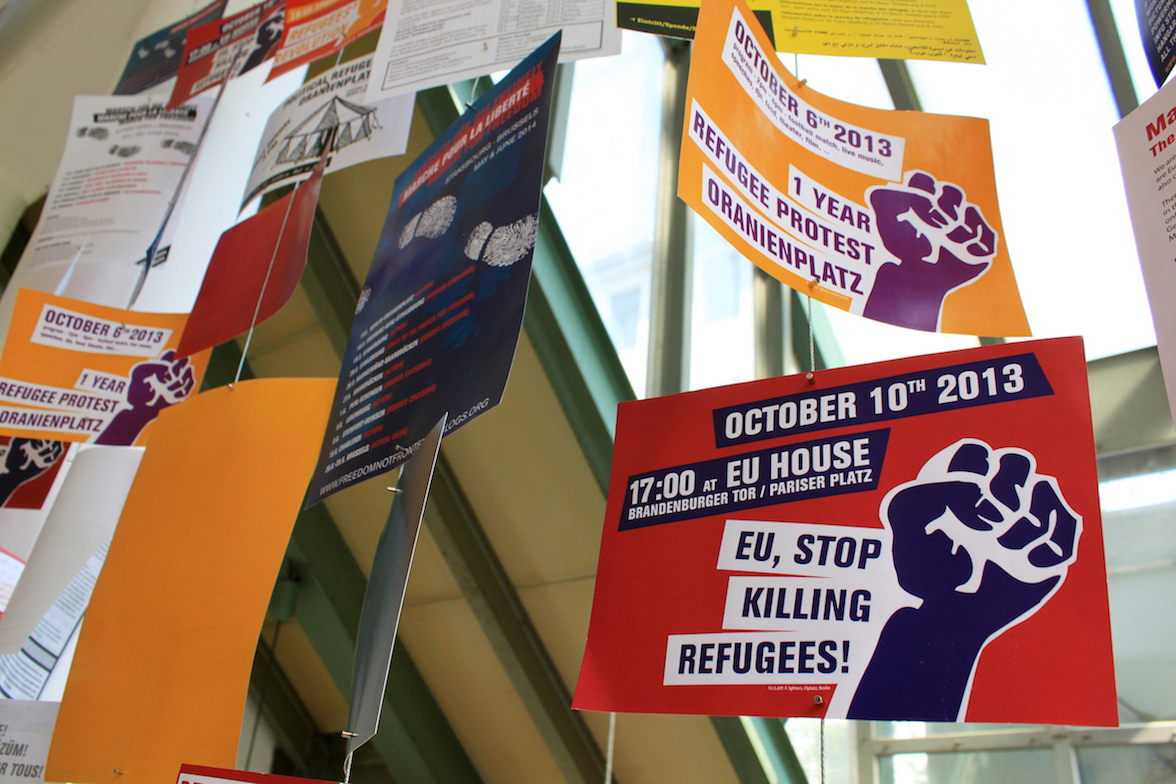

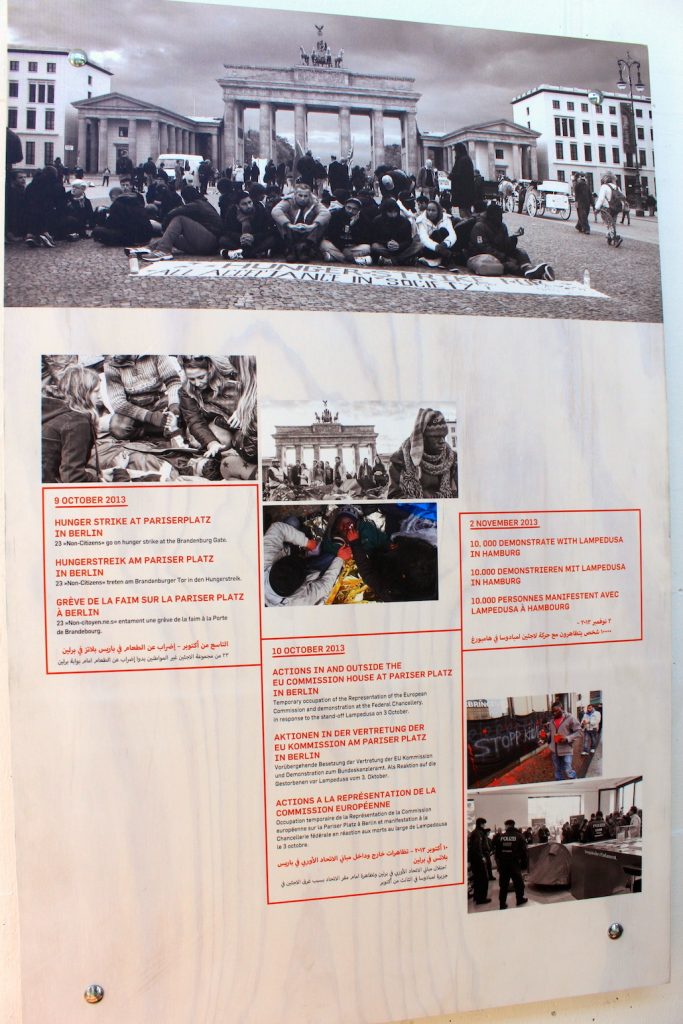

The panels mark important dates in the movement’s history.

The panels mark important dates in the movement’s history.

The movement’s main claims are: to grant all refugees political asylum, to stop deportations, to grant them the right to live where they want and the right to work. Huge political successes of the movement, so far, are the liberalisation of the “Residenzpflicht” in most federal states of Germany, an increase of the financial support for refugees and widespread replacement of the belittling meal vouchers with cash. Moreover, the demands of the refugees have been firmly anchored in the agenda of German media, politics and the public awareness. Ultimately, the refugee movement seeks to abolish the placement of refugees in isolated or shared accommodations, gain a legal claim to German language courses, certified translators and lawyers, to simplify the process for family reunions and to shorten the asylum procedures.

The movement’s main claims are: to grant all refugees political asylum, to stop deportations, to grant them the right to live where they want and the right to work. Huge political successes of the movement, so far, are the liberalisation of the “Residenzpflicht” in most federal states of Germany, an increase of the financial support for refugees and widespread replacement of the belittling meal vouchers with cash. Moreover, the demands of the refugees have been firmly anchored in the agenda of German media, politics and the public awareness. Ultimately, the refugee movement seeks to abolish the placement of refugees in isolated or shared accommodations, gain a legal claim to German language courses, certified translators and lawyers, to simplify the process for family reunions and to shorten the asylum procedures.

Refugees – A complex and diverse group: International Politics and Identity

The public actions of the refugees do not solely aim at making their claims heard and pressure the government. They also want to point out how German and EU foreign policies, arms deliveries and economic decisions are directly related to and responsible for the creation of refugees in their countries of origin. Hence, several embassies of oppressive governments that Germany deports to were occupied as well as German institutions. Accordingly, the exhibition links the local struggle in Berlin to other refugee movements in Europe, such as Brussels, Lampedusa and Greece. This “is not an interesting exhibition about interesting black people”, says Adam Bahar at the opening ceremony, this “is showing the deadly European migration politics”.

Bino Byansi Byakuleka opening the exhibition on 7 August 2015.

Bino Byansi Byakuleka opening the exhibition on 7 August 2015.

In order to network and unite with refugees all over the country, the movement organised bus tours to refugee centres, facilitated open conferences and even held a public trial against Germany. These public actions were regularly targeted by forceful police operations and racist attacks – using verbal and physical violence. The refugee women formed a separate Womenspace (International Womenspace) and joined the pre-existing initiative Women-In-Exile to raise awareness for the multiple discriminations and perils women face both outside and also within the refugee centres. The movement explicitly advocates solidarity with all oppressed and marginalised groups, particularly those whose reasons for seeking asylum are rarely recognised, such as the Roma people and persons who are in danger because they identify as LGBTIQ.

Banner expressing solidarity with LGBTQI, in front of FHXB-museum at exhibition opening.

Banner expressing solidarity with LGBTQI, in front of FHXB-museum at exhibition opening.

Kreuzberg – the heart and home of the movement

After the opening of the exhibition at the museum, the organisers move our group of visitors, refugees and supporters on to Oranienplatz. Here, Turgay Ulu and Bino Byansi Byakuleka evoke a sense of what the initial tent town once looked like, where the movement took roots and resisted eviction. But in April 2014, after lengthy negotiations with the new mayor Monika Hermann (Green Party), interior senator Frank Henkel (CDU) and integration senator Dilek Kolat (SPD), the movement was splitting up regarding a compromise offered by local authorities. Being promised a six-months “Duldung” (temporary toleration) and alternative accommodations, access to German courses and assessment of their vocational trainings, a faction from within the movement voluntarily disassembled the camp, left the school and the occupation of Oranienplatz ended.

The secured gate of Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule in Ohlauer Straße.

The secured gate of Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule in Ohlauer Straße.

After the suspension elapsed in summer 2014, however, most of the refugees were denied asylum and lost financial support and the right to stay in their alternative accommodations. Many moved to Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule to avoid deportation. Thanks to the solidarity of hundreds of local Berliners who organised sit-ins in front of school, the repeatedly announced forced eviction could be hindered and a fraction of the refugees was officially allowed to stay, whilst others were sent to other locations once more. The slogan of the refugees: You can’t evict a movement. The school is today still occupied by 24 men but their legal status is precarious, with temporary stay permits of three up to six months. No one apart from then can enter or visit the school – the gates are closed with heavy locks and security staff guards the premises.

Fatuma Musa Afrah speaks to us in front of the occupied school.

Fatuma Musa Afrah speaks to us in front of the occupied school.

In March 2015, the “Haus der 28 Türen” (House of the 28 Doors) on Oranienplatz was burnt down in an arsen attack. No one saw the perpetrators. No one was detained. No one was held responsible. The art project of the BEWEGUNG NURR (Florian Göpfert, Alekos Hofstetter und Christian Steuer) was built as a commemoration of all refugees that have died at European borders on their flight – the figure 28 represents the 28 EU-countries. Since the house was a symbol and event space for the refugee movement, speculations about the affiliation of the agents responsible for the arsen flourish. Anway, the movement has lost an important publicly visible landmark. Now, a permanent information point with one table has been set up on Oranienplatz instead, which is staffed each day from 3-9pm.

Self-representation vs. Respectability Politics

Before the exhibition opened, a controversy unfolded between the organisers on one side and a representative of donour Heinrich-Böll-Foundation and museum director, Martin Düspohl, on the other. The trigger was an exhibition text, formulated by Turgay Ulu from the Movement, which criticised Monika Hermann and the Green Party. It is entitled “What is the difference between Henkel and Hermann” and, in short, claims that whilst the political position of the CDU towards refugees was always clear, the Green Party pretended to support the refugees but betrayed them behind their backs. Whilst using liberal language and presenting itself as a humanitarian organisation, so the criticism continues, the Green Party left the refugees homeless, agreed to the “Asylrechtsverschärfung” (aggravation of the right of asylum) and co-signed military interventions.

Debate about the Hermann/Henkel text in front of the museum.

Debate about the Hermann/Henkel text in front of the museum.

The representative of Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, which is closely affiliated with the Green Party, and museum director Düspohl expressed their feeling that the text was a personal attack on Hermann. They also said they believed that such a statement would harm the movement. The answer from the movement was straightforward. “You want us to show our perspective, this is our perspective”, said Bino Byansi Byakuleka, remarking that the voice of the refugees is usually stifled or distorted in the public. Turgay Ulu added that it represented a jointly shared view within the whole movement and as such was vital to the exhibition as an honest account of its history and struggle. And another refugee shortly summes up in a serious tone: “We know politics because we are affected by it”.

________________

WE WILL RISE – Refugee Movement

Exhibition and Archive in Progress

Glass tower of FHXB Museum, Berlin

7 August to 30 October 2015

back to posts!